On Blade Runner, Advantageous, and Cyberpunk Gentrification

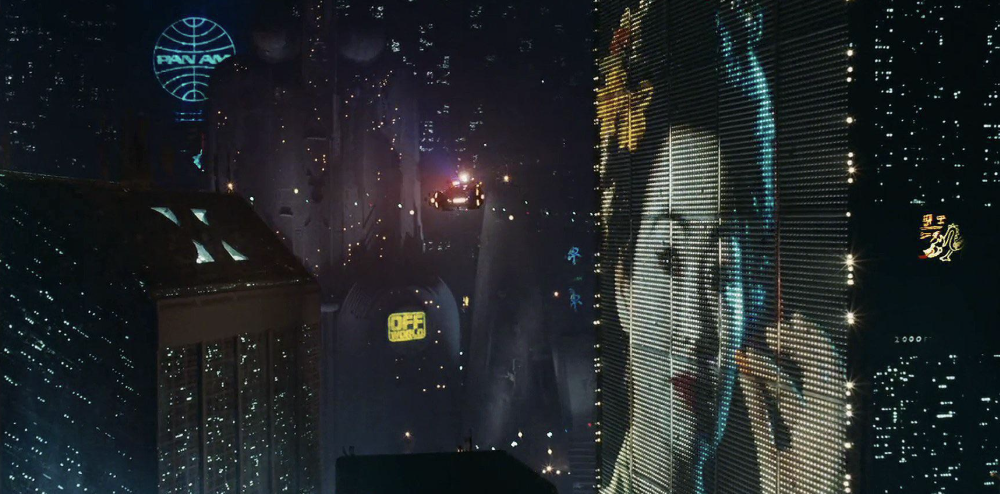

In the spring of 2008, a series of articles touted a Los Angeles real estate mogul and his ambitious revitalization project for the city—one that carried a decidedly dystopian influence. Holding up the now-iconic image of a geisha superimposed over plans for his downtown high-rises, Sonny Astani unveiled his vision to make the Tokyo-inspired setting of Blade Runner a partial reality.

These plans sparked both bemusement and horror. One columnist accused the exile from Tehran of seeing the film’s "Hobbesian vision of a future L.A." as a pleasant contrast to the Khomeini regime. Yet the controversy extended far beyond aesthetics. With Blade Runner's incept date a mere decade away, the ongoing U.S. housing crisis and subsequent recession served as stark reminders of the film’s themes of economic disparity.

Astani’s vision was neither new nor unprecedented. 20 years earlier, cultural historian Norman Klein observed that Blade Runner had already become "a paradigm for the future of cities," recounting at a 1990 Los Angeles public arts lecture how three out of five urban planners expressed their hope that Los Angeles would someday resemble the film’s aesthetic.

Now, over thirty years later, this cyberpunk-infused aspiration remains relevant, extending far beyond the city. The late Anthony Bourdain, for instance, was in the middle of plans to create a Blade Runner-themed food market in Manhattan’s rapidly developing far West Side, drawing inspiration from both the film’s set design and the bustling back alleys of Tokyo. Japan itself has become a hub of tourists, hoping to find the anime future in a land where fax machines remain in regular use.

As cities continue to evolve, the intersection of gentrification and cyberpunk raises complex questions. While some view these urban transformations as visionary, others see them as dystopian warnings come to life. Ridley Scott’s cinematic masterpiece remains an enduring blueprint for urban futurism, with developers highlighting the temporal and cultural contrasts when discussing its appeal. In an interview with the New York Times, Astani confessed to being "gripped by the notion of looming skyscrapers covered with moving images and graphics, and the layering of old and new structures,” while Bourdain found the chaotic, sensory impact of areas like Tokyo and Singapore captivating. However, as Klein notes, there is an unsettling lack of self-awareness regarding the admiration of these spaces, especially considering the impact of redevelopment on their existing residents:

"Two of the designers gave specific examples. They loved Santee Alley, a bustling outdoor market in the downtown garment center, also not far from the homeless district. Of course, the general area is slated for urban renewal anyway, so this was a safe comment. It is easy to root for the horse once it is off to the glue factory.”

A "transitional film" blending the "forties memorabilia of Lucas and Spielberg" with the aesthetic that emerged from William Gibson's novels and films like The Matrix and Ghost in the Shell, Blade Runner also serves as a critique of ongoing urban development. It highlights both the abandonment of progressive urbanism—leading to a workforce predominantly made up of minorities and the urban poor—and the rise of new high-rises driven by the repeal of height restrictions.

Writing on Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell, Wong Kin Yuen describes the aesthetic as "decadence, anarchy, and fantasy on the one hand, and a mistrusted, hyper high-tech reality.” These settings emphasize the core themes of cyberpunk, primarily questioning the fallibility of history and memory. Jane Chi Hyun Park narrows these themes down to inquiries about "what makes us ‘human’ in a heavily corporatized, media-saturated world" and how we distinguish between objects, places, and experiences from their mediated copies.

Cyberpunk's portrayal of Japan and the East has often been critiqued as reflecting Western ambivalence towards a technologically ascendant Japan in the 1980s. Morley and Robins argue that the nation is depicted as "the figure of empty and dehumanized technological power," representing a dystopian image of capitalist progress. Ueno Toshiya, discussing the popularity of anime and Ghost in the Shell, suggests this is indicative of a Western "complex about Japan," a projection of both envy and contempt.

A similar tension appears in the admiration developers express for areas like ethnic markets, which they romanticize for their "rude aesthetics" but also imagine as "safely barricaded between buildings hundreds of feet high.” This contradiction is evident in the appeal of such neighborhoods to gentrifiers, lured by "ethnic packaging" that offers an "outside community" experience perceived as unobtainable in the suburbs. As Sarah Schulman observes, these neighborhoods are deemed "good" or "safe" not for their diversity but because they are moving towards homogeneity, often making life more dangerous for the original inhabitants.

The results of urban development and gentrification in many cities make it clear that Blade Runner was always already a nostalgic film. The rise of the tech industry, which promised the future depicted in the film, has instead led to the darkened windows of Google company vans designed to hide the homeless, and to the displacement of working and middle-class residents. The reality of this future has been less chaotic and more a flattening, with ethnic restaurants and mom-and-pop businesses replaced by chain stores. As Klein observed, "Blade Runner helps us remember high urban decay at the moment before a community sank like a stone; or gentrified into something else.”

This realization prompts a reconsideration of how science fiction films might reimagine the future in light of these economic realities. How can they incorporate the influence of cyberpunk in reshaping urban landscapes and the displacement of long-term residents?

In January 2015, Jennifer Phang's Advantageous premiered at The Sundance Film Festival to critical acclaim. The film, an expansion of a 23-minute short, was criticized by some for being "wan-looking" and a "universe of such quietness and sterility that it’s difficult to care about its inhabitants.” However, such criticisms overlooked the film’s minimalist design, which enhances its narrative about inequality. Allusions to Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell serve as powerful metaphors for gentrification and displacement.

Director and co-writer Phang drew inspiration for the film from her experiences living in Washington Heights, a neighborhood undergoing rapid gentrification. She observed how financial and racial status impacted children's experiences with the world, contrasting the active learning of wealthier children with the anxiety of those from less privileged backgrounds.

Advantageous is set in 2041, when the population has reached 10.1 billion, the public school system has been dismantled, and unemployment is at 45 percent. The central character, Gwen Koh (Jacqueline Kim, who co-wrote the script) works as a spokesperson for a health company. Gwen is a single mother trying to ensure a better future for her daughter, Jules, in a world where women are undervalued. However, Gwen is soon informed by her employer that she will be replaced by a younger, more 'universal' type, prompting her to undergo a consciousness transfer to a younger, racially ambiguous body. This narrative echoes the themes of memory and identity found in both Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell but with a focus on the gendered dimensions of displacement and exploitation.

Gwen's forced abandonment of her ethnically Korean appearance in favor of a younger, more homogeneous look is a stark metaphor for gentrification. Her new identity as Gwen 2.0 embodies the erasure of both personal and historical identity, a process that mirrors the white-washing often seen in Hollywood and the displacement of marginalized communities in gentrifying neighborhoods. In this way, Advantageous critiques both the commodification of identity and the erasure of the histories that underpin such transformations.

As Michael Herzfeld writes, gentrification often invokes "the past" as a rationale for intervention, but the question remains: whose past is being preserved, and whose is being erased? This question is echoed in Ghost in the Shell, where a sanitation worker's memories of his daughter are revealed to be implants, reinforcing the theme of erasure of identity. In Advantageous, Gwen 2.0 experiences a similar revelation when she learns that her memories are not her own but those of her predecessor, highlighting the capitalist system’s role in creating these illusions of continuity and privilege.

As Schulman observes, gentrification fosters a "forgetful complacency" in the privileged, who replace the history of a neighborhood's original inhabitants with a distorted sense of themselves as timeless. This illusion of continuity is purchased at the cost of erasing the identities of those who came before.

Gwen's transformation into the face of the Center for Advanced Health and Living alludes to Blade Runner’s iconic cityscape, where a large video screen featuring a geisha symbolized the link between American corporate power and the "Orient." In Advantageous, her position as a spokeswoman parallels this imagery, but the film adds its own critique by centering Gwen, rather than a stereotypical representation of the "Orient," as the protagonist. This shift in focus critiques the commodification of identity and the relegation of women to background roles, while also addressing the loss of selfhood through gentrification.

The cityscape in Advantageous is minimalist and stark, contrasting with the more chaotic environments of Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell. In this future, hovercrafts and surveillance cameras further alienate the city's poor, who are exposed and vulnerable. Unlike the bohemian spaces in Blade Runner, which offered their inhabitants opportunities for survival, Advantageous presents a world where the marginalized are isolated and increasingly powerless.

In the world of Advantageous, food, like the city itself, reflects a loss of diversity and vibrancy. Unlike Blade Runner, where street kiosks evoke a sense of cultural richness, Advantageous shows a world where even the most intimate acts of eating are imbued with a sense of loss. When Gwen attempts to visit a familiar restaurant with her daughter, they find it closed; through the window, they can see the owner counting out her dwindling funds in frustration. The disappearance of places that once offered sanctuary and connection parallels the broader theme of gentrification, where the cultural fabric of neighborhoods is unraveled in the pursuit of profit.

Blade Runner and Advantageous are reflections of how gentrification and techno-Orientalism intersect with issues of identity and power, not only critiquing the social and economic consequences of urban renewal but also offering a needed exploration of how cultural narratives about the future are shaped by the past. Questions of collective memory and the loss of identity, along with the role privilege plays in a rapidly changing landscape, remind us that gentrification is not just about physical displacement but the erasure of stories and histories that do not fit within the dominant narrative. Like tears in rain, they are cautionary tales about forgetting.

Note, this is an older publication I’ve repurposed and updated to fit this format. Sources below.

Beiser, V. (2008, April 21). L.A. Real Estate Mogul Plans to Light Up Blade Runner Style Billboards. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2008/04/st-bladerunner/

California Department of Water Resources. (2010). California’s Drought: An Overview. Retrieved from http://www.water.ca.gov/waterconditions/docs/DroughtReport2010.pdf

Cathcart, R. (2008, May 21). A Developer’s Unusual Plan for Bright Lights, Inspired by a Dark Film. The

New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/21/arts/design/21blad.html

Chang, R. M. (Producer), & Phang, J. (Director). (2015). Advantageous. [Motion Picture]. United States : Film Presence.

Chayka, K. (2016, August 7). Same old, same old. How the hipster aesthetic is taking over the world. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/06/hipster-aesthetic-taking-over-world Child, B. (2015, April 15). Whitewashing row over Scarlett Johansson’s Ghost in the Shell role reignites.

The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/film/ 2016 /apr/ 15 /scarlett-johanssons-role-in-ghost-in-the-shell-ignites-twitter-storm

Corbyn, Z. (2014, February 23). Is San Francisco Losing its Soul? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/23/is-san-francisco-losing-its-soul

Deeley, M. & de Lauzirika, C. (Producers) & Scott, R. (Director). (1982). Blade Runner [Motion Picture].United States: Warner Brothers.

Dunn, M. (2015, May 19). Anthony Bourdain will transform his International Food Market into a scene from Blade Runner. News.com.au. Retrieved from http://www.news.com.au/technology/innovation/design/anthony-bourdain-will-transform-his-international-food-market-into-a-scene-from-blade-runner/news-story/12f49473e5d284300ab1f66834776b2e

Forster, L. (2004). Futuristic Foodways. In A.L. Bower (Ed.), Reel Food:Essays on Food and Film. 251–266. New York, NY. Routledge.

Geiger, D. (2015, May 12). Google gobbles up New York. Crain’s New York Business. Retrieved from http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20150512/REAL_ESTATE/150519959/google-gobbles-up-new-york-search-giant-poised-to-anchor-new-development-on-pier-57

Hackworth, J., & Reckers, J. (2005). Ethnic Packaging and Gentrification: The Case of Four Toronto Neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review, 41. 211–236.DOI: 10.1177/1078087405280859

Hassenger, J. (2015, June 25). Advantageous finds eerie plausibility in science fiction. The AV Club. Retrieved from http://www.avclub.com/review/advantageous-finds-eerie-plausibility-science-fict-221242

Kaye, B. (2015, May 16). Anthony Bourdain to open giant Blade Runner-themed food market in New York

City. Consequence of Sound. Retrieved from consequenceofsound.net/ 2015 . 05 /anthony-bourdain-to-open-giant-blade-runner-themed-food-market-in-new-york-city/

Klein, N. (1991). Building Blade Runner. Social Text, 28. 147-152. Duke University Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/466383

McNamara, K. (1997) Blade Runner’s Post-Individual Worldspace.

Contemporary Literature. Vol. 38. No. 3. pp. 442–446.

University of Wisconsin Press. Retrieved from http://jstor.org/stable/120897415-08-2016

Miller, S. (2014, May 19).The evangelical presidency: Reagan’s dangerous love affair with the Christian

right. Salon. Retrieved from

http://www.salon.com/2014/05/18/the_evangelical_presidency_reagans_dangerous_love_affair_with_

the_christian_right/( 162 ) Disadvantageous: Gentrification and The Cyberpunk Aesthetic 109

Mizuo, Y. (Producer), & Oshii, M. (Director). (1995). Ghost in the Shell [Motion Picture]. Japan: Bandai

Visual.

Morley, D., & Robins, K. (1995). Techno-Orientalism: Japan Panic. In Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Elec-

tronic Landscapes, and Cultural Boundaries. 147–173. New York, Routledge.

Park, J. (2005) Stylistic Crossings: Cyberpunk Impulses in Anime. World Literature Today, 79, 60-63. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40158943

Phang, J. (2015, June 23). The Mary Sue Interview: Advantageous’ Jennifer Phang. (L. Coffin, Interviewer).

The Mary Sue. Retrieved from http://themarysue. com/the-mary-sue-interview-advantagesus-jennifer-phang/

Rutten, T. (2008, January 30). L.A.’s Blade Runner Plans. The Los Angeles Times.

Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/2008/jan/30/opinion/oe-rutten30

Semerene, D. (2015, June 24). Advantageous. Slant Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/review/advantageous

Schulman, S. (2012). The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. 2012.

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Phang, J. (Writer), & Phang, J. (Director). (2012). Advantageous [Television Broadcast]. J. D. Thompson (Producer). Future States. United States : ITVS.

Ueno, Toshiya. Japanimation and Techno-Orientalism (n.d.). Retrieved September 15, 2016. http://www.t0.or.at/ueno/japan.htm

Wong, K. (2000). On the Edge of Spaces: “Blade Runner”, “Ghost in the Shell”, and Hong Kong’s Cityscape.

Science Fiction Studies, 27(1), 1–21. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4240846

Yu, Timothy. (2008). Oriental Cities, Postmodern Futures: “Naked Lunch”, “Blade Runner”, and “Neuro-mancer”. Melius, 33(4). 45-71. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20343507