On Words, Time Travel, and Losing a Parent

I never expected to fall in love with a Hallmark show. Having lived most of my adult life abroad, my only real brush with the brand is a faint memory of walking into a card store in the '80s, all ribbons and racks of sentiment (the building that once housed it now sits abandoned in the heart of downtown Portland). Mostly, I've gleaned my image of it from jokes and parody videos and twice-removed cultural references I've picked up online. That's the case with quite a few things: I know little about Wendy Williams other than that she was a talk show host who enjoyed tea.

So, no, I wasn't planning on getting sucked into The Way Home, Hallmark's foray into science fiction, or rather magical realism. It's cheesy in bits, and some of the dialogue could use another pass, but it's also a show that takes its time travel logic seriously, and like BtVS, it's refreshingly counterintuitive, refusing to drag certain storylines beyond their sell-by dates. But by Season 2, the show went from compelling to brilliant, transforming Colton — a character I initially found mawkish — into the linchpin of the narrative.

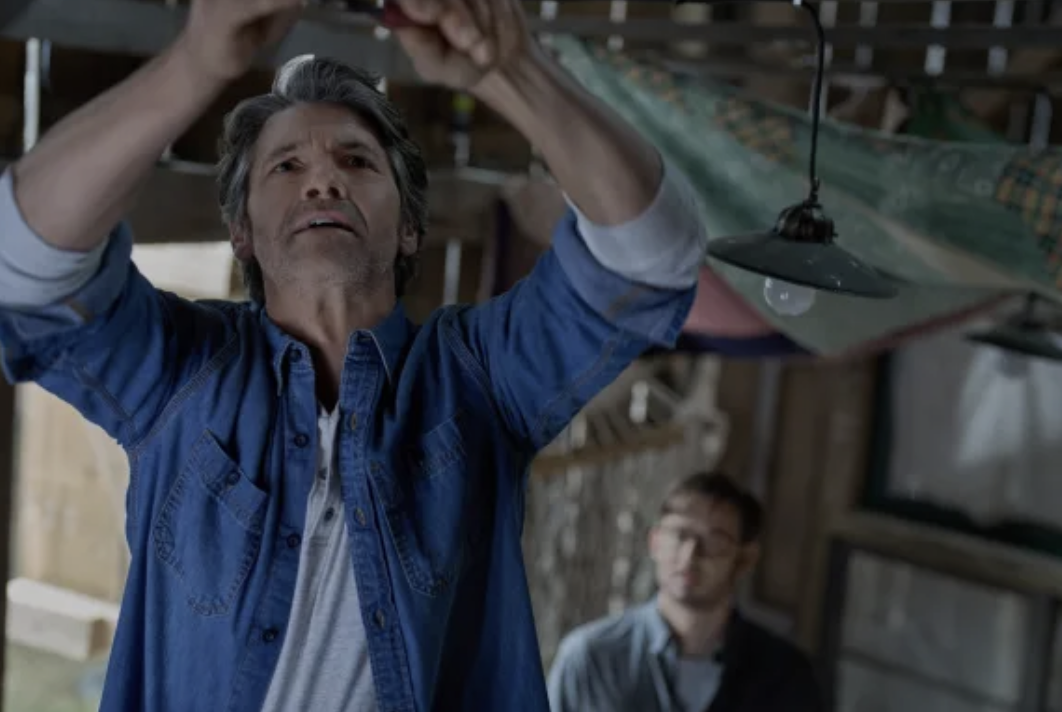

In Season 1, Landry is the ghost of Christmas past, a soft patriarch bordering on cloying. I’d assumed that Hallmark added him as a bone to traditional audiences, which yeah, they did do that—but it turns out they were doing a lot more. In Season 2, he's reliably present whenever Del requires comfort or Eliot experiences daddy issues, appearing in flashbacks or the past, and always, always with the right words. And then — a twist — Colton’s a time traveler, too. Like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, we wonder if he's been fine-tuning these interactions on a loop, calibrating the circularity of time toward those instants where they might have an impact.

In one sense, Colton is a writer’s wish-fulfillment fantasy, a chance to retrofit those thwarted reassurances and confessions into characters’ mouths. But in another, it’s a self-referentialism that transcends Hallmark winking at its own tropes—see Kat’s throwaway line about the career woman returning home. Instead, they've folded them into the mechanics of time travel.

Writers sometimes use tarot cards to draw on archetypes or shift the dynamics in the story, but here, they've taken the Hallmark card and slotted it into the arcana. The Fool, The Hanged Man, The Sap. Whatever he is, all his schmaltzy interactions from the previous seasons transcend surface sentimentality and take on genuine meaning. It’s dazzling, but it also made me think about the hollowness of the right words—how little comfort they offer even when you render them with care.

Colton can’t change the past. He’s left to his voice, and however refined his delivery may be in hindsight, he can’t be certain of its impact. Add the Paradox of Ineffectuality to that Grandfather dilemma.

My father died two years ago. A cancer that had gone into remission returned suddenly, carrying out its imperative in weeks. I canceled my classes and boarded a plane, missing his passing by a few hours. Days earlier, I had spoken to him over the phone while he was still lucid. We weren't sure about the timeline then, three months or three weeks. I told him I loved him, that he'd inspired me. We talked about Orwell (his favorite) and joked that he’d better not go religious at the last minute.

Later, my mother remarked that he'd told her I'd said "all the right things."

I’ll never really know what that meant.